|

| ©Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| The Alfred Jewel; photo by Richard M Buck via Wikimedia Commons |

(This post is a resource for my students ENGL 223-6, who will be reading a range of medieval English and Norse literature in translation. By no means does this post provide an exhaustive list of museum and web resources for the study of material culture in early England and France, but it’s a start, and it does present some visually beautiful and useful resources. The banner image is ©Trustees of the British Museum)

I was lucky enough to be able to visit a few of my favorite museums in Oxford, Paris and London last fall, where I was reminded of the power of seeing medieval objects in well curated settings — though online curation will have to suffice for this post. I encourage anyone who has the chance to go to these museums in person to do so. (I am very lucky and privileged to have gone once, let alone to revisit them!)

I went to the Ashmolean Museum, the Musée de Cluny and the British Museum over the course of a couple of weeks, in and around engaging in research at several libraries and archives. At the Ashmolean, I saw the “King Alfred’s Coins” exhibition. The Ashmolean is the home of the “Alfred Jewel,” which is currently on view with the “Coins” exhibition. The exhibition brings together a range of objects from around northern Europe from around the ninth century. No-one is exactly sure what the Alfred Jewel is, but the museum’s “Object of the Month” page tells us: “opinion has moved towards its being an aestel or pointer, used to follow the text in a gospel book in much the same way that the Yad continues to be used in the Jewish synagogue for reading the Torah.” You can see more images and read about the jewel here.

The Ashmolean also had part of the hoard discovered by James Mather in 2015. This is “an important Viking hoard [found] near Watlington in South Oxfordshire. It dates from the end of the 870s, a key moment in the struggle between Anglo-Saxons and Vikings for control of southern England,” according to the Ashmolean website. They also point out that “[t]he Watlington Hoard sheds new light on the conflict between Anglo-Saxons and Vikings, and on the relationship between the two great Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Mercia and Wessex.” You can learn more about the Vikings at the Smithsonian website, here.

Several other hoards have been uncovered in the last few years. The Staffordshire Hoard, which was discovered in 2009, is “the largest collection of Anglo-Saxon gold and silver metalwork ever found, anywhere in the world.” Images from that hoard are available here.

|

| Fibules_mérovingiennes_02 via Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Bird brooch, Merovingian; ©Trustees of the British Museum |

Finally for this post, at the British Museum I made a beeline for my favorite room: Room 41, The Sir Paul and Lady Ruddock Gallery (Sutton Hoo and Europe, AD 300–1100), where a wide range of objects like the Franks’ Casket (above) and objects from the Sutton Hoo ship burial (and hoards!). As the British Museum website tell us, “The centuries AD 300–1100 witnessed great change in Europe. The Roman Empire broke down in the west, but continued as the Byzantine Empire in the east. People, objects and ideas traveled across the continent, while Christianity and Islam emerged as major religions. By 1100, the precursors of several modern states had developed. Europe as we know it today was taking shape. Room 41 gives an overview of the period and its peoples. Its unparalleled collections range from the Atlantic Ocean to the Black Sea, and from North Africa to Scandinavia. The gallery’s centrepiece is the Anglo-Saxon ship burial at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk – one of the most spectacular and important discoveries in British archaeology.”

|

| Photograph by Mike Peel www.mikepeel.net). [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons |

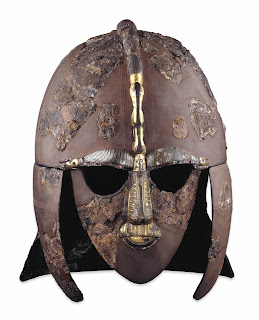

You can learn more about the Sutton Hoo burial mound and excavation at the National Trust website. Even better, you can see a shiny, high resolution image of what the rusty helmet to the right here probably looked like, and images of the remains of the burial boat and other objects.

|

| The Sutton Hoo helmet; ©Trustees of the British Museum |

The range of objects and the magnificent artistry I saw during these visits reminded me how cosmopolitan and sophisticated these early medieval cultures were. Objects found at the Prittlewell burial site also confirm this. (You can download a paper about the Prittlewell burial site here.) While these cultures were not yet entirely global, there was far more cultural interaction than many people today realize; the “successor states” that arose after the fall of Rome were complex and dynamic.

This is just a brief overview, but the visuals and basics included here will give my 223 students a sense of the complex cultures and contexts for reading poems and stories like Beowulf and the Saga of the Volsungs.

|

| ©Trustees of the British Museum; Sarre Brooch (disk brooch); necklace; bead; early Anglo-Saxon; early Byzantine; 7th (early) Sarre |